Pitfalls of best practices

— software engineering — 8 min read

Good advice comes with a rationale so you can tell when it becomes bad advice. If you don’t understand why something should be done, then you’ve fallen into the trap of cargo cult programming, and you’ll keep doing it even when it’s no longer necessary or even becomes deleterious. — Raymond Chen

The software industry has an extensive repertoire of so-called “best practices” that, in theory, should produce net positive results. Some of these practices are inherently useful but suffer in how they are disseminated, adopted, and applied. Meanwhile, some “best practices” inherently have a negative ROI.

The raison d'être of this essay is to surface some of the perils of mindlessly using “best practices”. Pragmatically, “best practices” serve as a good baseline. Unfortunately, too often, they are used as a substitute for thinking (critically).

The essay is organized into three sections, each focusing on a reoccurring issue I have observed with “best practices”. To make each section concrete, I have included real-life examples from my experiences. I will conclude the essay by trying to build a case for the current state of affairs and explore some ideas for improvements.

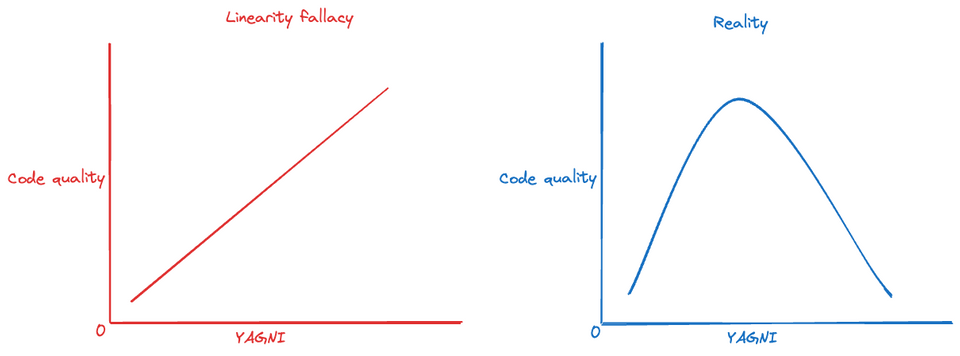

Linearity fallacy

Not every curve is a straight line.Nonlinear thinking means which way you should go depends on where you already are — Jordan Ellenburg

The relationship between two things is seldom linear. A linearity fallacy is committed when you incorrectly assume a linear relationship relates two variables. There is such a thing as “too much of a good thing”. I will expand on this point with test coverage in the following paragraphs.

Engineering teams often get presented with a fait accompli to increase their (unit) test coverage to X% (where X is some arbitrary number like 80%). Whenever I hear this, I like to troll by asking why 80%? Why not 81%? The point of my question is to point out the absurdity of such a number that is typically obtained on a questionable basis.

Test coverage is indistinguishable from superstition when not tethered to something real and verifiable. It’s often blindly assumed that increasing coverage would increase confidence in the codebase. The reality is some types of tests like change detector tests provide negative value because they impede evolvability without testing anything valuable. These types of tests are just more sophisticated incarnation of verify(sha256(old_code) == sha256(new_code)).

Because of the combinatorial explosion with the state space of any non-trivial software, it’s practically impossible to test all possibilities. This fact, coupled with an untethered belief in testing, gets teams stuck in a loop where they (mindlessly) add more tests in response to quality issues. While it might be the case that tests are lacking, an underutilized approach is to simplify the system by removing accidental complexities. I will buttress this point with two anecdotes:

I worked on a project where we over-indexed on “clean architecture”. We separated concerns into three different Android services that communicated with each other by passing messages. On paper, this looked beautiful. However, in reality, some of our services were unexpectedly getting killed because we were operating in developing markets with cheap Android devices with stringent battery optimizations. The quality of our app suffered because all services had to be active for our app to work. Every week or so, we discovered a new edge case in the field; we handled it and wrote lots of tests for it. We were climbing a local maximum for months. The more optimal strategy was to question our constraints: “Do we actually need three services?”. We rewrote the code with only one service, and all the problems disappeared. We deleted the tests, too, as we had handled the problem by not having the problem.

Another team I worked with had two implementations of a specific contract.

Implementation Awas responsible for ~80% of reported bugs. Somewhat paradoxically,implementation Aalso had a test coverage of ~70%, whereasimplementation Bwas below 20%. Instead of figuring out whyimplementation Ahad more defects thanB, we were all tasked with improving our coverage to some magic number.

I’m not against test coverage. I want teams to think from first principles before embarking on a month-long crusade to improve test coverage. If we scale these tests, would we have detected any of the last ten issues we encountered? Have we peaked this strategy? Is this even an effective testing strategy (i.e., are we getting more confident in our code)?

I will close this section by succinctly exploring the over-use of some other practices:

| Practice | Over-use |

|---|---|

| DRY | Typically leads to creating the wrong abstractions. The wrong abstraction can be more expensive than duplication. |

| YAGNI | Can lead to Tactical programming. Tactical programming increases complexity due to myopic design decisions that are usually subpar. |

| Microservices | Can create unnecessary complexity. Krazam’s skit humorously highlights this problem. |

| Small functions | Commonly leads to shallow modules. Shallow modules or functions don’t help much in the battle against complexity because the benefit they provide (not having to learn about how they work internally) is negated by the cost of learning and using their interfaces. |

Conflation

Conflation is the practice of treating two distinct concepts as one, which produces errors or misunderstandings.

Conflation is harmful because it produces a double whammy of wastefulness and stagnation. e.g. A (more) useful way X of doing Y emerges, but the people indoctrinated in practice Z resist it as “not following best practices”. These arguments typically boil down to a non sequitur like X!=Z (of course! It doesn’t!). When these people are the loud majority, they can have a (temporary) chilling effect on a sector.

Of course, not everything old needs to be changed, and not everything new needs to be adopted (and vice versa). It’s usually a mistake to change something before understanding why it was there in the first place (see Chesterton’s fence). However, familiarity can also hinder us from seeing a new idea independently in its own light.

Facebook faced this resistance during the early days of React. Pete Hunt responded to the React critics in this talk. He distinguished between “Separation of concerns” and “Separation of technologies”. The former gives you the desired outcome of low coupling and high cohesion. The latter tends to result in high coupling and low cohesion.

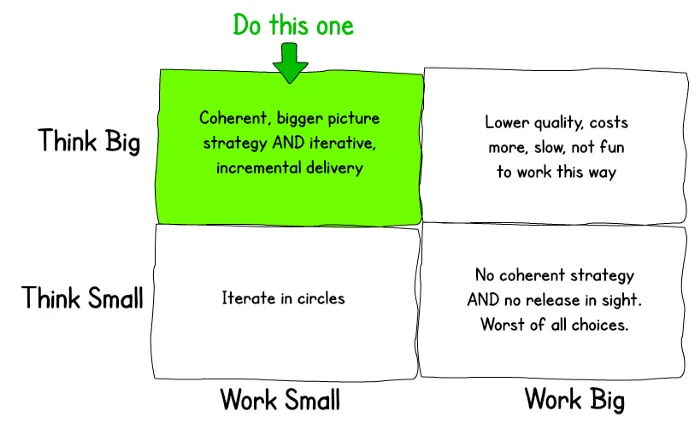

Another example that comes to mind is the adoption of Agile. I have worked in many teams that strongly conflate “acting small” with “thinking small”. If, for example, you are designing a product in an established space, there are features you can almost certainly know you will need. You don’t need to build them! But not considering how they will at least fit in your architecture is a recipe for future pain (unless you plan on doing a rewrite).

Think big, work smallOut of context

One of the biggest traps for smart engineers is optimizing something that shouldn’t exist. — Elon Musk

Typically, the variant of an idea that has gained virality has been stripped of its original context. This phenomenon might be because recall is lossy, and it’s easier to evangelize soundbites. I will double-click this point in the following paragraphs with three examples.

Example 1

The Android team introduced ConstraintLayout to handle complex layout use cases and placate some of the shortcomings of other layouts like LinearLayout. It wasn’t long until ConstraintLayout got “best practice” status. My team instead chose to use LinearLayout as the substrate for a server-driven UI library we built, and we got smoke from engineers who claimed we were not performant because we were not following “best practices”.

If we had capitulated to the pressure to follow this “best practice” blindly, the ROI would have been a net negative: the performance claim was false (because the UI we had wasn’t amenable to the instances where ConstraintLayout is more performant), and we would have had more production defects (because of the complexity of constraints).

Herein lies the rub with the everyday use of the phrase “best practices”: “The best way to do X in Y context” gets lossy compressed into “the best way to do X”. Eventually, people start applying the “best way” everywhere. They incur all the cost of the “best way” without reaping any of its benefits because the context was never relevant to them.

Example 2

Programmers waste enormous amounts of time thinking about, or worrying about, the speed of noncritical parts of their programs, and these attempts at efficiency actually have a strong negative impact when debugging and maintenance are considered. We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%. — Donald Knuth

Commonly, you hear this as “premature optimization is the root of all evil” (Knuth’s quote was prematurely optimized). The problem with this shorter version of the quote is that it often inspires the following behaviors:

- Performance is often an afterthought because people believe they can optimize later. This sentiment is not always true. Some decisions are spread through the codebase and can’t be surgically changed easily. This optimize-later style can also lead to more complexity when optimizations are superimposed into the existing design (e.g., unnecessary threading or caching because individual ops are so slow).

- False dichotomy between performance and code quality. Performant code can have an equivalent quality to its less efficient counterpart.

- Inability to distinguish between projects where performance is critical and projects where it isn’t.

Example 3

Crash-only software refers to computer programs that handle failures by simply restarting without attempting any sophisticated recovery. Too often, when a team is introduced to this idea, it is overused and underutilized. The excerpt below explains this mistake in more detail.

Another mistake is the overuse of the crash/restart “hammer.” One of the ideas in crash-only software is that if a component is behaving strangely or suffering some bug, you can just crash it and restart it, and more than likely, it will start functioning again. This is often faster than diagnosing and fixing the problem by hand, so it is a good technique for high-availability services. Some programmers overuse the technique by deliberately writing code to crash the program whenever something goes wrong, when the correct solution is to handle all the errors you can think of correctly, and then rely on crash/restart for unforeseen error conditions. Another overuse of crash/restart is that when things go wrong, you should crash and restart the whole system. One tenet of crash-only system design is the idea that crash/restart is cheap - because you are only crashing and recovering small, self-contained parts of the system. — Crash-only software: More than meets the eye

Conclusion

The problem with the name “best practice” is a similar problem with the name “clean code”. The names are typically used to connote something positive, even when they just encode subjectivity. e.g., Some groups might consider code that adheres to the Locality of Behavior (LoB) principle as not being clean or following best practices. Different solutions have different tradeoffs, so articulating exactly why something is better is more productive than relying on opaque names (i.e., names that don’t have a clear agreed-upon definition).

During my research for this essay, I tried to figure out why some “best practices” are still widely used, even when they are not particularly useful. The excerpts below might provide some explanation:

- “Best practice is about collective liability: When following best practice, a failure is all our fault. Otherwise, you own that failure alone.” — Nathants

- “One reason a practice’s inefficiency may be difficult to spot is because when it came into existence, it was beneficial. But when circumstances have changed, and it has become inefficient, nobody remembers. Because everybody is now doing it, it is difficult to spot that doing it differently would be better.” — HBR

- Dan Luu pointed out how hard it is to communicate nuance at scale. This might explain why some “best practices” are worded in an absolute way.

My goal with this essay is to implore people to think critically. It’s harder to eliminate unnecessary complexity when it’s masqueraded as “best practice”. Don’t you want to follow “best practice”?

A model is a simplification or approximation of reality and hence will not reflect all of reality. […] “**all models are wrong, but some are useful.**” — Model Selection and Multimodel Inference

Guidelines, conventions, and good practices don’t need to be flawless; they only need to be useful in your context. They are not free, so you must ensure their value outweighs their cost. If you genuinely try something and it feels like it doesn’t make sense, it probably doesn’t. Don’t fall for false consensus via information cascade, but also, don’t be too eager to dismiss an idea because you think you are different (you probably aren’t).

Context always matters. I have tried to build a case against mindlessly following “best practices”. However, there are cases where it makes sense to do so. e.g., for legal reasons (collective liability), lack of time to make an informed decision (time crunch), unfamiliar domain, etc.

I hope that one day, we will have a living repository to host and proliferate good patterns, their history, the context they matter in, their tradeoffs, symptoms of overuse/underuse, intellectually honest conversations, etc.

In this age, as organizations seek to be more efficient, they are best served by minimizing practices that cost so much yet provide no meaningful value.