The Design of Everyday Things — Book Summary & Notes

— notes, summary — 21 min read

This is my summary and notes from The Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman. Please use the link if you decide to buy the book after reading this as it contains my affiliate code. Thanks.

- Good design is harder to notice than poor design, partly because good designs fit our needs so well that the design is invisible, serving us without drawing attention to itself.

- Bad design screams out its inadequacies, making itself very noticeable.

Chapter 1: The psychopathology of everyday things

- Two of the most important characteristics of good design are:

- Discoverability: Is it possible to even figure out:

- What actions are possible and

- Where and how to perform them?

- Understanding: What does it all mean? How is the product supposed to be used? What do all the different controls & settings mean?

- Discoverability: Is it possible to even figure out:

- The major areas of design relevant to this book are:

- Industrial design:

- Emphasizes form & material.

- Definition: “The professional service of creating and developing concepts and specifications that optimize the function, value, and appearance of products and systems for the mutual benefit of both user and manufacturer” — the Industrial Design Society of America's website.

- Interaction design:

- Emphasizes understandability & usability.

- The focus is on how people interact with technology.

- The goal is to enhance people's understanding of what can be done, what is happening, and what has just occurred.

- It draws upon principles of psychology, design, art, and emotion to ensure a positive, enjoyable experience.

- Experience design:

- Emphasizes emotional impact.

- The practice of designing products, processes, services, events, and environments with a focus placed on the quality and enjoyment of the total experience.

- Industrial design:

- Design is concerned with how things work, how they are controlled, and the nature of the interaction between people and technology.

- Engineers are experts in technology & are trained to think logically; However, they are limited in their understanding of people.

- Much of a product is designed by engineers; their designs are often too logical because they believe all people must think this way.

We have to accept human behavior the way it is, not the way we would wish it to be.

Human-centered design (HCD)

- Human-centered design is a design philosophy — it starts with a good understanding of people and the needs that the design is intended to meet.

- This understanding comes primarily through observation — people are often unaware of their true needs or the difficulties they encounter.

- HCD principle is to avoid specifying the problem as long as possible but instead to iterate upon repeated approximations.

- This is done through rapid tests of ideas, and after each test modifying the approach and the problem definition.

Fundamental principles of interaction

- Great designers produce pleasurable experiences.

- Discoverability results from the appropriate application of six fundamental psychological concepts:

- Affordances

- Signifiers

- Constraints

- Mappings

- Feedback

- Conceptual model

Affordances

- An affordance is a relationship between the properties of an object and the capabilities of an interacting agent (like a human or robot) that determine how the object could possibly be used.

- Examples:

- A chair affords (“is for”) support and, therefore, affords sitting.

- Glass affords transparency.

- The presence of an affordance is jointly determined by the qualities of the object and the abilities of the agent that is interacting.

- Anti-affordance is the prevention of interaction.

- Affordances exist even if they are not visible. For designers, their visibility is critical — visible affordances provide strong clues to the operations of things:

- A flat plate mounted on a door affords pushing.

- Knobs afford turning, pushing, and pulling.

- Slots are for inserting things into.

- Balls are for throwing or bouncing.

- Perceived affordances help people figure out what actions are possible without the need for labels or instructions.

Signifiers

- Affordances are the possible interactions/actions between an interacting agent (like humans) and an object.

- Some affordances are perceivable, others are invisible.

- Signifiers communicate what actions are possible and where the action should take place (i.e: how it should be done).

- Signifiers are any perceivable indicator (signals like signs, labels, drawings, audio, etc) that communicates appropriate behavior to a person.

- Some signifiers are perceived affordances, such as the handle of a door or the physical structure of a switch.

- Perceived affordances can be ambiguous.

- The holes in a scissor are both:

- Affordances — they allow the fingers to be inserted

- Signifiers — they indicate where the fingers are to go.

- Example:

- Being able to swipe right/left to the next Tinder profile is an affordance

- Signaling the gestures and their meaning with icons or an animation is a signifier.

Mapping

- Mapping is a technical term, borrowed from mathematics, meaning the relationship between the elements of two sets of things.

- Mapping is an important concept in the design and layout of controls and displays. When the mapping uses spatial correspondence between the layout of the controls and the devices being controlled, it is easy to determine how to use them. E.g:

- To move an object up, move the control up.

- Vertical position is appropriate for representing intensity or amount: people associate moving the hand up with more, and moving it down with less.

- Groupings and proximity are important principles from Gestalt psychology that can be used to map controls to function:

- Related controls should be grouped together.

- Controls should be close to the item being controlled.

Feedback

- Feedback is communicating the results of an action.

- Feedback must be:

- Immediate — delays lead to people leaving (annoyed) which is wasteful if the system continues while they are gone.

- Informative — it must convey that something has happened, what happened, and what we should do about it.

- Poor feedback can be worse than no feedback because it’s:

- Distracting

- Uninformative

- Irritating and anxiety provoking

- Too much feedback can be more annoying than too little — it leads people to ignore them all or disable them if possible — which is dangerous because critical feedback is missed.

- All action must be confirmed, but feedback needs to be prioritized:

- Unimportant information is presented un-obstructively.

- Important information is presented in a way that captures attention.

Conceptual models

- A conceptual model is an explanation, usually highly simplified, of how something works. It doesn’t have to be complete or even accurate as long as it is useful.

- Simplified models are valuable only as long as the assumptions that support them hold true.

- The conceptual models concerned with here are the simple mental models in the minds of the end-users — not the complex ones found in technical manuals or books.

- Mental models are the conceptual models in people’s minds that represent their understanding of how things work.

- A single person can have multiple models of an item, each dealing with a different aspect of its operation, and some of them being in conflict.

- Conceptual models are valuable:

- In providing understanding

- In predicting how things will behave

- And in figuring out what to do when things go wrong.

System image

- The designer’s conceptual model is the designer’s conception of the look, feel, and operation of a product.

- The system image is what can be derived from the physical structure that had been built (including documentation, instructions, signifiers, …). It’s the combined product information available to the user.

- The user’s mental model is developed through interaction with the product and its system image.

- Designers expect the user’s model to be identical to theirs, but because they can’t communicate directly with the user, the burden of communication is with the system image.

- Good conceptual models are the key to understandable & enjoyable products; Good communication is the key to good conceptual models.

The paradox of technology

The paradox of technology and the challenge for a designer:

The same technology that simplified life by providing more functions in each device also complicates life by making the device harder to learn or use.

The design challenge

- Design requires the cooperative effort of multiple disciplines — hence, great design requires great designers and great management.

- Each discipline has a different perspective on the relative importance of the many factors that make up a product (often biased by the discipline’s distinct contribution):

- Marketing: Price + features

- Engineers: Reliability

- Manufacturing: We have to use our existing manufacturing plants.

- Support: Solve these problems that we often get called about.

- Design: You can’t put all that together and still have a reasonable product.

- Every discipline concern is usually right — the successful product tries to address all of them.

- The attributes of a product that customers primarily focus on are dynamic:

- In the store: they focus on price, appearance, and prestige value.

- At home: they pay more attention to functionality and usability.

- Maintainability comes into play during repairs or extended usage.

Notes

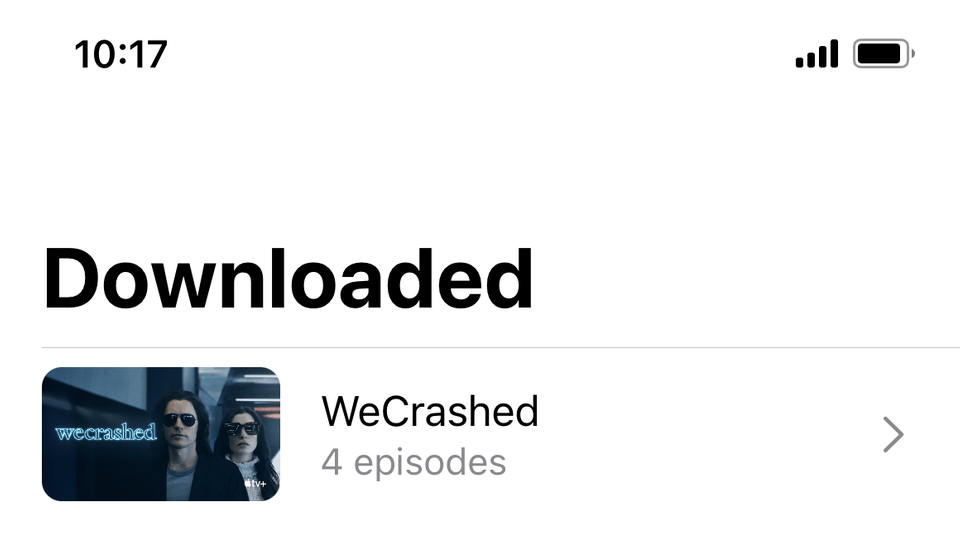

- The communication in non-happy paths of modern products is often inadequate:

- When I’m offline or during a connectivity issue, most products show a fallback UI. However, they fail to communicate my current state. My router could have been disconnected without my knowledge and I will spend a few seconds trying to figure out why the product UI is different now. A simple “you are offline” would suffice.

Apple TV offline state — it provides no indication of a connectivity issue.

Apple TV offline state — it provides no indication of a connectivity issue. - Poor loading indicators: Are you still making progress with my request or is it stuck? This is why I don’t like the shimmer loading effect so much.

- Generic error message: Should I try again? What really happened and can I do anything about it?

- When a call disconnects, is it a problem on my side or on the other side?

- When I’m offline or during a connectivity issue, most products show a fallback UI. However, they fail to communicate my current state. My router could have been disconnected without my knowledge and I will spend a few seconds trying to figure out why the product UI is different now. A simple “you are offline” would suffice.

Chapter 2: The psychology of everyday actions

- There are two parts to an action:

- Doing — Executing the action and

- Interpreting — then evaluating the results.

- When people use a thing, they face two gulfs:

- The Gulf of Execution

- How do I work this thing? What can it do? What can I do with it?

- Bridged through signifiers, constraints, mappings, and a conceptual model.

- The Gulf of Evaluation

- What happened? Is this what I wanted?

- Bridged through feedback and a conceptual model.

- The Gulf of Execution

- The action cycle:

- Goal (form the goal)

- Plan (the action; execution)

- Specify (an action sequence; execution)

- Perform (the action sequence; execution)

- Perceive (the state of the world; evaluation)

- Interpret (the perception; evaluation)

- Compare (the outcome with the goal; evaluation)

- Root cause analysis

- Reconsider the true goals behind a user’s immediate or superficial goal

- Harvard Business School marketing professor Theodore Levitt once pointed out, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!” Buying a drill is an intermediate goal. The true goal might be that they want to hang shelves on the wall.

- Emotion is highly underrated. In fact, the emotional system is a powerful information processing system that works in tandem with cognition. Cognition attempts to make sense of the world: emotion assigns value.

- Systems of cognition:

- Subconscious: Fast; Automatic; Controls skilled behavior.

- Conscious: Slow; Controlled; Invoked for novel situations: when learning, when in danger; when things go wrong.

- Three levels of processing:

- Visceral: subconscious

- Most basic level of processing (aka “the lizard brain”).

- Fast and automatic.

- For designers, the visceral response is about immediate perception — attracted or repulsed?

- Behavioral: subconscious

- Learned skills triggered by situations that match the appropriate patterns.

- Aware of the high-level actions but the details are handled at a subconscious level (from memory and habit).

- For designers, the most critical aspect of the behavioral level is that every action is associated with an expectation. Feedback loops are critical here.

- Reflective: conscious

- Where conscious thought and decision-making reside, as well as the highest level of emotions

- Cognitive, deep, & slow.

- Attempt to understand cause and effect and make predictions occurs here.

- Reflective memories are often more important than reality.

- Visceral: subconscious

- Design must take place at all levels: visceral, behavioral, and reflective.

- People are inclined to assign causal relations when two things occur in succession.

- Learned helplessness: Situations in which people experience repeated failure at a task. As a result, they determine that the task cannot be done (at least by themselves).

- The corresponding questions to ask in the action cycle:

- What do I want to accomplish?

- What are the alternative action sequences?

- What action can I do now?

- How do I do it?

- What happened?

- What does it mean?

- Is this okay? Have I accomplished my goal?

- Well-designed products result in users who can answer all of the above questions while they use the product.

Notes

- I always thought that turning a thermostat to the highest setting quickly heats up a room. This chapter explained that this is a flawed mental model. TIL.

Chapter 3: Knowledge in the head and in the world

- Precise behavior can emerge from imprecise knowledge (in the head) because:

- Not all the knowledge for precise behavior has to be in the head — it can be distributed — partly in the head and in the world.

- Natural constraints in the world restrict the possible behavior: An object's features like screw threads or depressions define the possible relationship with other objects or what actions can be performed on it. This is an example of knowledge in the world.

- Cultural constraints and conventions are learned artificial restrictions on behavior that reduces the set of likely actions. This is an example of knowledge in the head.

- Lastly, great precision of knowledge is seldom required.

- Whenever knowledge needed to do a task is readily available in the world, the need for us to learn it (completely,) diminishes.

- Designers can put sufficient perceivable cues (signifiers, physical constraints, and natural mapping) into a product’s design (knowledge in the world) such that good performance is attained even without prior (complete) knowledge of the product.

- People function through their use of two kinds of knowledge:

- Declarative knowledge:

- Is knowledge of.

- It includes the knowledge of facts and rules. E.g: “Stop at red traffic lights.

- It’s easy to write and teach.

- It doesn’t need to be true.

- Procedural knowledge:

- Is knowledge how.

- It’s difficult to write down and difficult to teach. It’s best taught by demonstration and best learned through practice. This is because it’s largely subconscious, residing at the behavioral level of processing.

- Declarative knowledge:

- Relying on knowledge in the world to compensate for incomplete knowledge in the head is susceptible to environmental changes that can make the combined knowledge inadequate.

- Psychological research suggests that people only maintain partial descriptions of the things to be remembered.

- People learn to discriminate among things by looking for distinguishing features. This is historical baggage — people get confused when a new item is introduced that “breaks” the learned distinguishing feature, like introducing a similar-looking coin.

- Constraints simplify memory.

- Two classes of memory:

- Short-term or working memory (STM):

- automatically retains a limited amount of the most recent experiences or material that is currently being thought about.

- About 5-7 items is the limit of STM.

- Susceptible to distractions.

- Design implication: Don’t count on much being retained in STM.

- To maximize the efficiency of working memory, it’s best to present different information over different modalities: sight, sound, touch (haptics), hearing, spatial location, and gestures.

- Long term memory (LTM):

- Memory for the past.

- Get & Put ops takes time.

- Capacity is unknown.

- Experiences are not remembered as an exact recording; rather, as bits and pieces that are reconstructed and interpreted each time we recover the memories, which means they are subject to all the distortions/biases and changes that the human explanatory mechanism imposes upon life.

- Sleep seems to help LTM.

- Short-term or working memory (STM):

- The most effective way of helping people remember is to make it unnecessary.

- Two categories of how people use their memories and retrieve knowledge:

- Memory for arbitrary things: The items to be retained seem arbitrary, with no meaning and no particular relationship to one another or to things already known. E.g: The alphabets.

- Memory for meaningful things: The items to be retained form meaningful relationships with themselves or with other things already known.

- Conscious thinking takes time and mental resources; Well-learned skills bypass the need for conscious oversight and control.

- Experts minimize the need for conscious reasoning.

It is a profoundly erroneous truism, repeated by all copy-books and by eminent people when they are making speeches, that we should cultivate the habit of thinking of what we are doing. The precise opposite is the case. Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them.

— Alfred North Whitehead, 1911. - Prospective memory: the task of remembering to do some activity at a future time.

- Memory for the future: Denotes planning abilities, the ability to imagine future scenarios.

- Two aspects to a reminder:

- The signal — knowing that something is to be remembered.

- The message — remembering the message itself.

- Natural mappings are those where the relationship between the controls and the object to be controlled is obvious.

- Three levels of mapping, arranged in decreasing effectiveness as memory aids:

- Best mapping: Controls are mounted directly on the item to be controlled.

- Second-best mapping: Controls are as close as possible to the object to be controlled.

- Third-best mapping: Controls are arranged in the same spatial configuration as the objects to be controlled.

- What mapping is natural is largely dictated by culture.

Tradeoffs between knowledge in the world and in the head

| Knowledge in the world | Knowledge in the head |

|---|---|

| Information is readily and easily available whenever perceivable. | Material in working memory is readily available. Otherwise considerable search and effort may be required. |

| Interpretation substitutes for learning. How easy it is to interpret knowledge in the world depends upon the skill of the designer. | Requires learning, which can be considerable. Learning is made easier if there is meaning or structure to the material or if there is a good conceptual model. |

| Slowed by the need to find and interpret the knowledge. | Can be efficient, especially if so well-learned that it is automated |

| Ease of use at first encounter is high | Ease of use at first encounter is low. |

| Can be ugly and inelegant, especially if there is a need to maintain a lot of knowledge. This can lead to clutter. Here is where the skills of the graphics and industrial designer play major roles. | Nothing needs to be visible, which gives more freedom to the designer. This leads to a cleaner, more pleasing appearance—at the cost of ease of use at first encounter, learning, and remembering. |

Notes

- The author talked about how many things are just cultural artifacts that can vary from place to place. E.g:

- Scrolling a window vs scrolling the text: Do you scroll up to scroll down or scroll down to scroll down?

- The future is typically depicted as being forward. However, some cultures claim it’s behind — as you can’t see what’s behind, you also can’t see the future.

- This got me questioning so many things like why was green chosen to mean go?

Chapter 4: Knowing what to do: Constraints, Discoverability, & Feedback

- Four kinds of constraints:

- Physical constraints:

- Constrain possible operations.

- More effective & useful if they are easy to see & interpret, for then the set of actions is restricted before anything has been done; Otherwise, a physical constraint prevents a wrong action from succeeding only after it has been tried.

- E.g: A square peg cannot be used with a round hole.

- Cultural constraints:

- Each culture has a set of allowable actions for social situations.

- E.g: red means stop.

- Semantic constraints:

- Semantics is the study of meaning.

- Semantic constraints are those that rely upon the meaning of the situation to control the set of possible actions.

- E.g: In Lego bike pieces, a windshield is meant to block wind from a rider’s face and therefore must be placed in front of the rider.

- Logical constraints:

- Using reason to determine the possible actions.

- E.g: if there are two bulbs and two switches, once the first switch is used, the second one must control the other bulb that didn’t turn on.

- Physical constraints:

- The lack of clear communication among the people and organizations constructing parts of a system is perhaps the most common cause of complicated, confusing designs. A usable design starts with careful observations of how the tasks being supported are actually performed, followed by a design process that results in a good fit to the actual ways the tasks get performed. The technical name for this method is task analysis. The name for the entire process is human-centered design (HCD).

- Forcing functions:

- A form of physical constraint that forces the desired behavior: situations in which actions are constrained so that failure at one stage prevents the next stage from happening.

- In the field of safety engineering, forcing functions shows up under other names, in particular as specialized methods for the prevention of accidents. Three such methods are:

- Interlocks: An interlock forces operations to take place in proper sequence. A dead man switch is a form of interlock that prevents operation when the operator is incapacitated.

- Lock-ins: A lock-in keeps an operation active, preventing someone from prematurely stopping it. E.g: Prompts that prevent a user from exiting without saving or consciously discarding their work.

- Lockouts: A lockout prevents someone from entering a space that is dangerous, or prevents an event from occurring.

- People invariably object and complain whenever a new approach is introduced into an existing array of products and systems. Conventions are violated: new learning is required.

The merits of the new system are irrelevant: it is the change that is upsetting.

- Consistency in design is virtuous. It means that lessons learned with one system transfer readily to others. On the whole, consistency is to be followed. If a new way of doing things is only slightly better than the old, it is better to be consistent. But if there is to be a change, everybody has to change. Mixed systems are confusing to everyone. When a new way of doing things is vastly superior to another, then the merits of change outweigh the difficulty of change.

- Just because something is different does not mean it is bad.

- Standardization is indeed the fundamental principle of desperation: when no other solution appears possible, simply design everything the same way, so people only have to learn once.

- Standards should represent the psychological conceptual models, not the physical mechanics.

- Standards simplify life for everyone, but also tend to hinder future development.

- Skeumorphic: incorporating old ideas or paradigms into new technologies (even when they play no functional role). Skeuomorphism is a helpful way to transition from old to new technologies.

Chapter 5: Human error? No, bad design

Error occurs for many reasons. The most common is in the nature of the tasks and procedures that require people to behave in unnatural ways — staying alert for hours at a time, providing precise, accurate control specifications, all the while multitasking, doing several things at once, and subjected to multiple interfering activities. Interruptions are a common reason for errors, not helped by designs and procedures that assume full, dedicated attention yet that does not make it easy to resume operations after an interruption.

75-95% of industrial accidents are caused by human error.

Root cause analysis: investigate the accident until the single, underlying cause is found.

Most attempts to find the cause of an accident are flawed for 2 reasons:

- Most accidents do not have a single cause: there are usually multiple things that went wrong, multiple events that, had any one of them not occurred, would have prevented the accident. What James Reason calls the “Swiss cheese model of accidents”.

- The root cause analysis stops as soon as a human error is found.

When root cause analysis discovers a human error in the chain, its work has just begun: now we apply the analysis to understand why the error occurred, and what can be done to prevent it.

Treat all failures in the same way: find the fundamental causes and redesign the system so that these can no longer lead to problems.

Root cause analysis is intended to determine the underlying cause of an incident, not the proximate cause.

The Five Whys: Japanese procedure for getting at root causes (originally developed at Toyota). The goal is to keep moving the inquiry deeper even after a reason has been found: ask why that was the cause.

Deliberate violations: cases where people intentionally violate procedures and regulations. These happen for different reasons:

- Routine violations occur when noncompliance is so frequent that it is ignored.

- Situational violations occur when there are special circumstances (example: going through a red light "because no other cars were visible and I was late'").

Although violations are a form of error, these are organizational and societal errors, important but outside the scope of the design of everyday things.

Human error is defined as any deviance from “appropriate” behavior.

Types of errors:

Slips:

- The goal is correct but the required actions are not done properly.

- Occurs when a person intends to do one action and ends up doing something else.

- Paradoxically, slips occur more frequently to skilled people than to novices — Because experts perform tasks “automatically” and slips result from a lack of attention to a task.

- Types of slips:

- Action-based slips: The wrong action is performed. Three action slips relevant to design:

- Capture slips:

- Instead of the desired activity, a more frequently or recently performed one gets done instead: it captures the activity.

- E.g: “I was using a copying machine, and I was counting the pages. I found myself counting, “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, Jack, Queen, King.” I had been playing cards recently.”

- Designers need to avoid procedures that have identical opening steps but then diverge.

- Description-similarity slips:

- Error results from similar targets.

- Example: “A former student reported that one day he came home from jogging, took off his sweaty shirt, and rolled it up in a ball, intending to throw it in the laundry basket. Instead, he threw it in the toilet.”

- Designers need to ensure that controls and displays for different purposes are significantly different from one another.

- Mode-error slips:

- Occurs when a device has different states in which the same controls have different meanings.

- Example: Turning off the wrong device in your home entertainment system.

- Designers must try to avoid modes, but if they are necessary, the equipment must make it obvious which mode was invoked.

- Capture slips:

- Memory-lapse slips:

- Memory fails, so intended action is not done or its result not evaluated.

- E.g: Forgetting to turn off the gas burner after cooking.

- The immediate cause of most memory lapses is interruptions.

- Ways to combat:

- Minimize the number of steps.

- Provide clear vivid reminders.

- Utilize forcing functions.

- Action-based slips: The wrong action is performed. Three action slips relevant to design:

Mistakes:

- Occurs when the wrong goal is established or the wrong plan is formed.

- Types of mistakes:

- Rule-based mistake:

- The person appropriately diagnosed the situation, but then decided upon an erroneous course of action.

- Rule-based mistake:

- Knowledge-based mistake:

- The problem is misdiagnosed because of erroneous or incomplete knowledge.

- Example: Weight of fuel was computed in pounds instead of kilograms.

- The best solution to knowledge-based situations is to be found in a good understanding of the situation, which in most cases also translates into an appropriate conceptual model.

- Memory-lapse mistakes:

- Occurs when there is forgetting at the stages of goals, plans, or evaluation.

- Usually caused by interruptions.

- These are mistakes, not slips because the goals and plan become wrong.

- Design cures are the same as memory-lapse slips.

Checklists are powerful tools, proven to increase the accuracy of behavior and reduce error, particularly slips and memory lapses.

It’s bad design to impose a sequential structure to task execution unless the task itself requires it.

Design lessons from the study of errors:

- Adding constraints to block errors

- Undo

- Confirmation and error messages: Requiring confirmation before a destructive action is executed. Even when the user proceeds with the action, if possible try to make it reversible, e.g: When a user chooses to discard their changes even after a confirmation prompt, the system can silently & temporarily still save the file if it’s small enough.

- Sensibility checks: Check that the requested operation is sensible.

Resilience engineering is a paradigm for safety management that focuses on how to help people cope with complexity under pressure to achieve success. It strongly contrasts with what is typical today — a paradigm of tabulating error as if it were a thing, followed by interventions to reduce this count. A resilient organization treats safety as a core value, not a commodity that can be counted. Indeed, safety shows itself only by the events that do not happen! Rather than view past success as a reason to ramp down investments, such organizations continue to invest in anticipating the changing potential for failure because they appreciate that their knowledge of the gaps is imperfect and that their environment constantly changes. One measure of resilience is therefore the ability to create foresight — to anticipate the changing shape of risk.

Chapter 6: Design thinking

- Design thinking is a process that takes the original problem statement as a suggestion, not a final statement. Then it iteratively attempts to determine what basic, fundamental (root) issue needs to be addressed. Once that is determined, a wide range of potential solutions are explored.

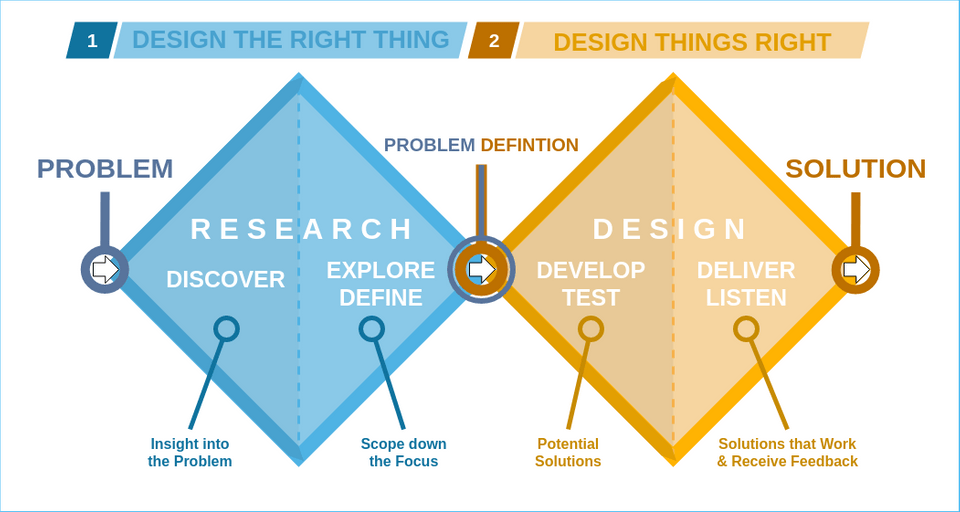

- The Double-Diamond Model of Design:

- Has two phases:

- Finding the right problem: Start with an idea, and through the initial design research, expand (or diverge) the thinking to explore the fundamental issues. Only then is it time to converge upon the real, underlying problem.Finding the right solution: Similarly, use design research tools to explore (or diverge into) a wide variety of solutions before converging upon one.

Photo credit: Digi-ark — Wikipedia.

Photo credit: Digi-ark — Wikipedia.

- Finding the right problem: Start with an idea, and through the initial design research, expand (or diverge) the thinking to explore the fundamental issues. Only then is it time to converge upon the real, underlying problem.Finding the right solution: Similarly, use design research tools to explore (or diverge into) a wide variety of solutions before converging upon one.

- Has two phases:

- The four different activities of Human-Centered Design are iterative — each cycle through the stages makes some progress. These activities are:

- Observation — Design research supports both diamonds of the design process:

- The first diamond, finding the right problem, requires a deep understanding of the true needs of people.

- Once the problem has been defined, finding an appropriate solution again requires a deep understanding of the intended population, how those people perform their activities, their capabilities, and prior experience, and what cultural issues might be impacted.

- Idea generation — While generating potential solutions, follow these three rules:

- Generate numerous ideas so you don’t get fixated on one or two ideas too early in the process.

- Be creative without regard for constraints. Avoid early dismissal of ideas — Even crazy ideas can contain creative insights that can be extracted and used in the final idea selection.

- Question everything: Quite often a solution is discovered through “stupid questions”, through questioning the obvious.

- Prototyping — Prototyping during the problem specification phase is done mainly to ensure that the problem is well understood. If the target population is already using something related to the new product, that can be considered a prototype. During the problem solution phase of design, then real prototypes of the proposed solution are invoked.

- Testing — testing is done in the problem specification phase to ensure that the problem is well understood, then done again in the problem solution phase to ensure that the new design meets the needs and abilities of those who will use it.

- Observation — Design research supports both diamonds of the design process:

- Design and marketing research are complementary but focus on different things:

- Design wants to know what people really need and how they will use a product.

- Marketing wants to know what people will buy and how purchasing decisions are made.

- In HCD, iteration is the repetition of the observe-generate-prototype-test cycle with the aim of achieving continual refinement and enhancement.

- The hardest part of designing is getting the requirements right, which means ensuring that the right problem is being solved, as well as that the solution is appropriate. Requirements made in the abstract are invariably wrong. Requirements produced by asking people what they need are invariably wrong. Requirements are developed by watching people in their natural environment.

- Activity-centered design: Focuses on activities, not the individual person. Let the activities define the product and its structure.

- The HCD process describes an ideal. But practice and reality can be messier and more chaotic.

In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.

- Norman’s Law of product development: “The day a product development process starts, it is behind schedule and above budget.”

- The design process must address numerous constraints like:

- Products have multiple, conflicting requirements: Designers must please their clients which are not always the end users.

- Designing for special people: There is no such thing as the average person.

- Stigma problem: Most devices designed to aid people with particular difficulties fail because people do not wish to advertise their infirmities.

- The best solution to the problem of designing for everyone is flexibility.

Notes

- I like the idea that engineers and other members of the development process are also users that designers should consider in the design process. They are users of the output of the design process.

Chapter 7: Design in the world of business

- Basic ways by which manufacturers compete:

- Price

- Features

- Quality

- Speed

- Two forms of product innovation:

- Incremental innovation: Follows a natural, slow evolutionary process. Less glamorous, but more common.

- Radical innovation: More glamorous, but rarely successful. Upends existing paradigms when successful.

- Radical innovation changes lives and industries. Incremental innovation makes things better. We need both.

- Radical innovation can get you on a point at some global best possible hill. From there, incremental innovation gets you to the highest point of that hill.

- Featuritis: Feature creep. Factors that contribute to feature creep:

- Existing customers want more features or capabilities.

- Competing companies add new features that create competitive pressures to match those offerings.

- Market is saturated: most people who want the product already have it. Adding enhancements will cause people to want to upgrade.

- New products are invariably more complex, more powerful, and different in size than the first release of a product.

- In her book "Different", Harvard professor Youngme Moon argues that it is this attempt to match the competition that causes all products to be the same. When companies try to increase sales by matching every feature of their competitors, they end up hurting themselves. After all, when products from two companies match feature by feature, there is no longer any reason for a customer to prefer one over another

- Technology changes rapidly, but people and culture change slowly.

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

The more things change, the more they are the same.- Ideas take a long time to traverse the distance from conception to successful product.

- Stigler’s law: the names of famous people often get attached to ideas even though they had nothing to do with them.

- The world of product design offers many examples of Stigler’s law. Products are thought to be the invention of the company that most successfully capitalized upon the idea, not the company that originated it.